Hacer una isla

In a studio visit leading up to this exhibition, I was having a conversation with the artist Alejandra Venegas about, well, let’s call it the nature of nature, and I was reminded of a passage in Norbert Wiener’s book, “The Human Use of Human Beings.”

“As entropy increases, the universe, and all closed systems in the universe, tend naturally to deteriorate and lose their distinctiveness, to move from the least to the most probable state, from a state of organization and differentiation in which distinctions and forms exist, to a state of chaos and sameness. … But while the universe as a whole, if indeed there is a whole universe, tends to run down, there are local enclaves whose direction seems opposed to that of the universe at large and in which there is a limited and temporary tendency for organization to increase. Life finds its home in some of these enclaves.”

The tendency toward sameness, for me, was an incredibly beautiful way to understand chaos and the nature of entropy. Seen as such, we’re not so much acting against willing agents of disorder as we are all rebelling against a universal inevitability, constantly taking actions both futile and necessary in order to exist.

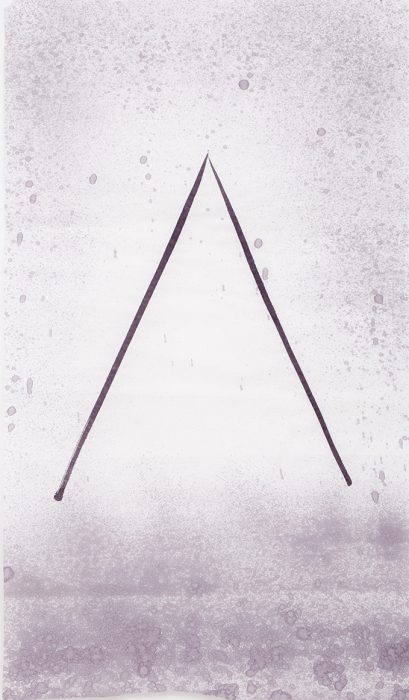

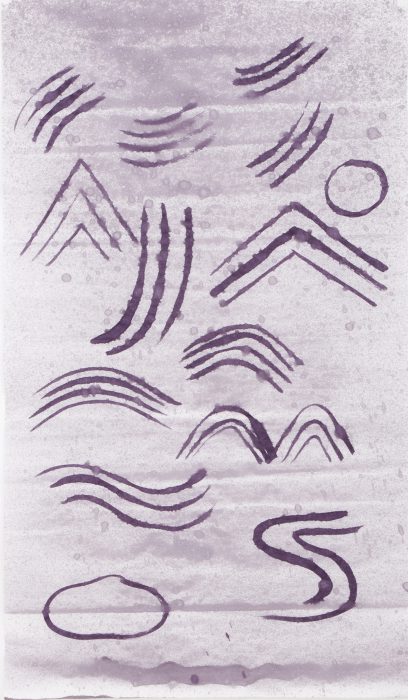

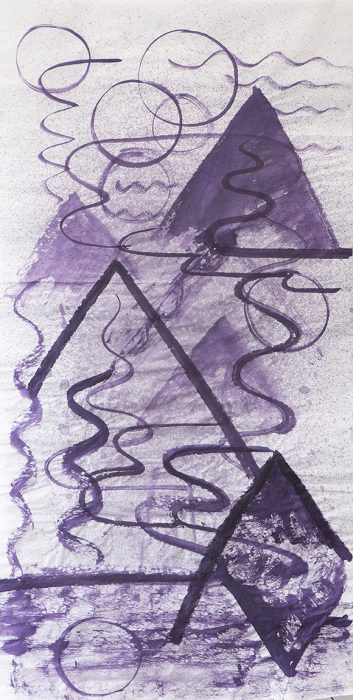

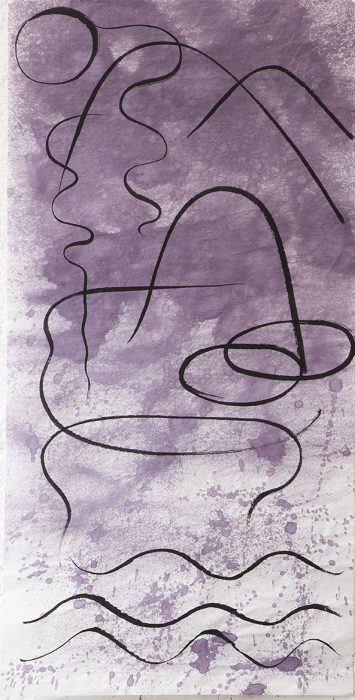

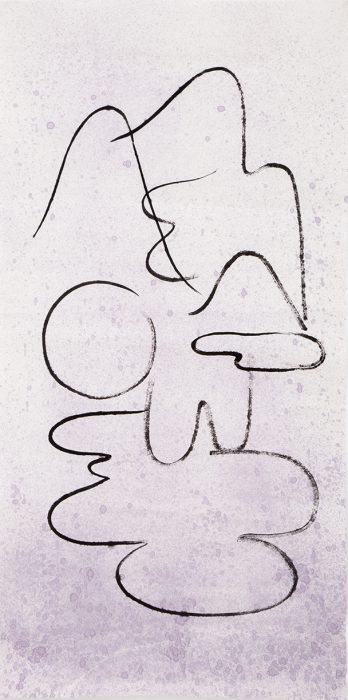

Alejandra Venegas has her home and studio in a village on the outskirts of Mexico City, surrounded by lush mountainous landscapes, which have gradually been transformed amidst the relentless expansion of the city. In her series, Pintura de montaña agua (“mountain water painting”), she reconstructs memories and images of these landscapes through a finite, combinatory set of lines, forms and gestures. Both dynamic and spontaneous, her painting practice has become for her a tool to intuitively understand a changing reality.

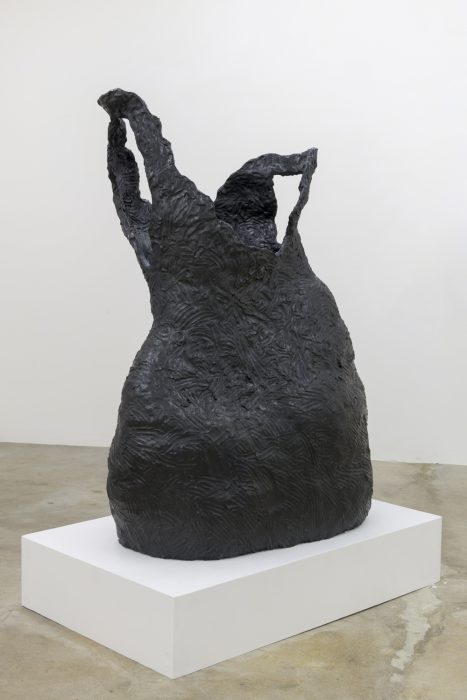

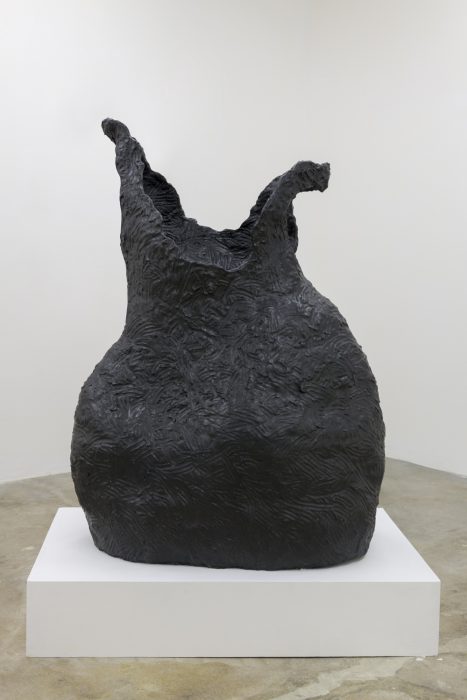

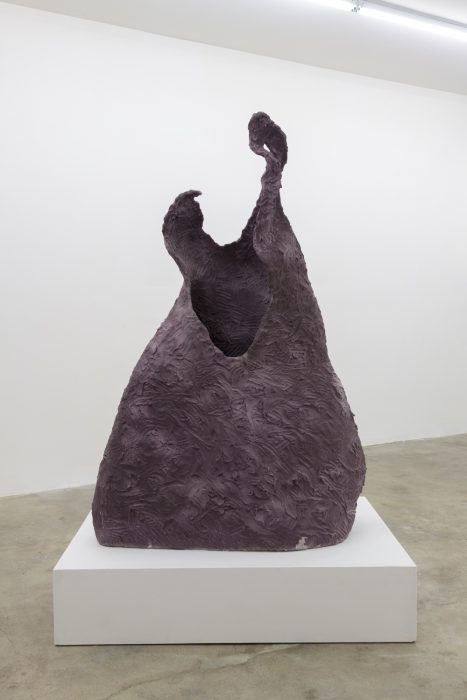

Anabel Juarez was born in the state of Michoacan, Mexico, but has been living in California since she was 15 years old. Her two coil-built ceramic sculptures, Musa (“Muse”) and Musa en Negro (“Muse in Black”), suggest garments atop larger-than-life female torsos. Figurative without figures, these works capture an ecstatic and liberatory lightness despite their literal and symbolic weight, reappropriating an object that represents not only female form but also female labor in the infamously exploitative garment industry.

I titled this show Hacer una isla, or “To make an island” in English, because both artists’ practices capture for me a willing resistance — against literal representation, against the arrow of time, against the urbanization of nature, against the colonization of female bodies — and I saw in each of these works an island of purpose in the middle of an indifferent ocean. Each one is, for me, an emotive, elegant gesture of defiance.

While writing this text, I returned to Wiener’s essay, specifically to the passage I mentioned above. Reading a bit further, I encountered the following line with an atypically dramatic punch for Wiener. Affirmative to the point of becoming prescriptive, it seems to me an appropriate way to conclude: “Life is an island here and now in a dying world.”

— Brett W. Schultz